Review: CK Williams’ ‘Wait’ by Sean O’Brien

Wait by CK Williams

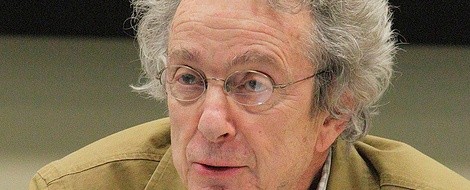

CK Williams continues to search for the good in America.

In “The Foundation” from Wait, CK Williams nominates Walt Whitman as a founding inspiration – “my giants, my Whitman, my Shakespeare, my Dante / and Homer”. He has also written a study of Whitman’s work. Certainly the great democratic poet’s influence is often apparent in Williams’s writing, but where some have been rendered prolix and prosaic by the song of the open road, Williams writes from an agonised temperamental opposition to Whitman’s expansive optimism: Williams is a pessimist who longs to feel otherwise, to believe, to do something with the burden of guilt and regret that is no lighter in his 74th year, and to retain a margin of faith in America as a society capable of good.

“Still Again: Martin Luther King, April 4 2008”, imagines King on a journey through contemporary America, horrified, heartbroken, yet resisting despair at 2 million in jail, at violence and ignorance, the connivance of the state and “faceless amoral money flowing like lava / only the market knows best the wise market the theorists cry the cunningly conscious / benevolent market the congressmen and their lobbyist all driven by greed mindless heartless / for all now the heartless money with its infinite sinkholes of infinite greed . . .” The pitch of this lament recalls Allen Ginsberg, and aspects of Williams’s own early poems. Here, for a few moments, he removes – to great but probably unrepeatable effect – the subtle checks and balances that anchor his mature work.

Robert Lowell, Louis Simpson and James Wright address comparable problems in American life, but Williams is like none of these highly individual elder poets. He is much more talkative and discursive; he is not primarily interested in figurative language; and while his poems are often powerfully concluded he seems almost to avoid quotable, epigrammatic endings such as Simpson’s “To the Western World”, where “Grave by grave we civilise the ground”. A Williams poem is not fixated on its own ending as a lyric poet might be; the ending serves the complete poem rather than signalling in shy triumph to the reader: look, I’ve pulled it off again.

Williams’s one faith is that things can be said, that subjects can be talked about, that poetry can seek to clarify as much as to beguile. His poems sometimes undertake philosophical inquiries whose effect can be both alarming and very funny. “All But Always” addresses the insoluble problem whereby consciousness cannot account for or encompass itself. Over a single, beautifully constructed, 36-line sentence, divided into three sections as though to give musical rests and an appearance of the calm the reader may be ceasing to feel, Williams proceeds by a tightening series of qualifications to his final inquiry about “this /mechanism of yours”: “if in fact you weren’t certain what to call / the thing – your mind, your self, your life? / What if indeed it was your mind, your self. / your life? What then, what then?” What indeed?

Sentence construction, one of the more neglected features of the poetic arsenal, is Williams’s great strength, his Ancient Mariner-like power to claim and hold the reader’s uncomfortable but rewarded assent. Developed in particular in the long lines for which Williams first came to attention a generation back, this power of construction serves to clarify at the same time as to include, to guarantee commitment to the matter in hand, and to lend its own extensive music as a source of authority. A non-believer, Williams both longs at times to believe and to be free of the desire to do so. The moral basis of his thought, as he is only too aware, derives from the Judaeo-Christian tradition he would like to escape: he has, for example, a sense of sin in the mistreatment of others. In this light, the heartbreaking comedy of “Assumptions” is both an exposure of the irrationality of belief and a demonstration of the tenacity of the longing, despite all the evidence, to embrace it:

That there is an entity, vast, omnipotent but immaterial, inaccessible to all human sense save hearing;

that this entity has a voice with which it can, or at least could once, speak, and in a possibly historical

but credible even if mythic past it did speak, to a small group of human beings, always male.

That not only did these primordial addressees receive the entity’s disclosures with perfect accuracy,

they also transcribed them (writing them down as they were spoken but no matter if years later)

literally, with precision, and no patching of gaps with however inspired imaginative spackle.

What differentiates Williams’s approach from the intolerant atheism now so widely abroad is that he does not assume that his own enlightenment is a personal virtue or evidence of superiority, for like it or not (and given its brutal political consequences Williams clearly doesn’t like it), religion is a disposition unlikely to be outgrown, any more than the skeleton can be outgrown, because, he suggests, it serves the powers we allow to govern us.

There is much else to commend the book, though it could lose a third of its length comfortably. There is a raw, rank sense of ageing masculinity alongside the absurd yet oddly heartening persistence of sexual triggers. There are elegies, observations of the natural world colliding with human observers, and a rich, complex poem about the death of Paul Celan. Williams is writing as well as ever.

This review was originally published on 15th January 2011.

External Links

Please note that NCLA can not be held responsible for the content of external websites. If you discover a dead link, or would like to add further links relating to this content to the list, please use the comments section below to contact us.

The original review at The Guardian online.

Sean O Brien on the British Council’s literature site.

C. K. Williams’ website.