‘Carolyn Forché’

– An essay by Robert Hampson

Professor Robert Hampson, from Royal Holloway, University of London, writes about Carolyn Forché’s The Country Between Us, which was re-published in 2019 by Bloodaxe Books.

This essay is part of the 2020 Inside Writing showcase.

It was with her second book of poems, The Country Between Us, that Carolyn Forché came to prominence. With this successful attempt to marry the personal lyric with the impulse to witness, Forché reached out to (and found) a wide audience.

Forché’s poetry of witness is recognisably in an American tradition of poetic witnessing that includes Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony (1934) and Holocaust (1975), based on court records, and Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead (1938), a hybrid work based on miners’ testimony and personal reportage in relation to the ‘Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster’, a case of corporate negligence in which hundreds of workers died of silicosis after being required to mine for silica without the proper protective equipment. However, it is Denise Levertov, with her earlier attempt to shift from the personal lyric to the witnessing of the American war in Vietnam, who is Forché’s direct precursor. Indeed, Levertov hailed Forché as ‘a poet who’s doing what I want to do’ – namely, ‘creating poems in which there is no seam between personal and political, lyrical and engaged’.

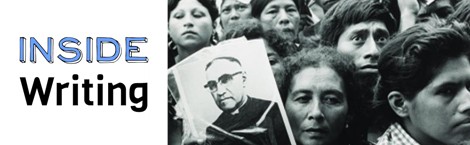

The opening section of The Country Between Us, ‘In Salvador, 1978-80’, was the product of Forché’s time in that country as an observer and human rights activist prior to, and during, the outbreak of the Civil War. It is dedicated to Monsignor Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of El Salvador, who had spoken out against poverty, social injustice and torture – and was assassinated by a right-wing death squad in March 1980 while celebrating mass. This sequence of seven poems traces a journey – from California to El Salvador and back; from Californian complacencies through various knowledges to the reverse culture shock of return – to political solidarity and the problem: what can or should the poet do with such knowledges.

The opening poem occupies a liminal position: it looks back to California (and its residents listening to the wind in the lemon trees, not attending to ‘the cries of those who vanish’ south of the border) and anticipates the possibilities of Forché’s own kidnap or ‘disappearance’ if she crosses the border. The second poem, ‘The Island’, is dedicated to the Salvadorean-Nicaraguan poet and novelist, Claribel Alegría, and focuses on her life. The third poem, ‘The Memory of Elena’, merges two times, past and present, as the calm of Elena’s Sunday lunch is invaded by memories of a murdered husband. The short prose narrative ‘The Colonel’ is the darkest of these central texts: a flat description of a banal domestic scene and a boring dinner ends, unexpectedly, with their host dumping a sack of human ears on the table, giving vent to a foul-mouthed rejection of human rights, and concluding with the taunt: ‘Something for your poetry, no?’

The poem ‘Return’ returns to this challenge. It is set up as a dialogue between the poet and her friend. Back in California, the poet is marked by her experiences in El Salvador: she jumps at ‘every tire blow-out’; she is wary of ‘every strange car near the house’. She also experiences a sense of alienation from American men. The poem concludes with her friend chiding her for the self-indulgence of her sense of powerlessness. The colloquial phrase she uses ‘not that your hands, as you / tell me, are tied’ furthers this critique as it picks up Forché’s initial fears of being kidnapped, being forced to ‘lead our lives with our hands / tied together’. This unsettling shift between a dead metaphor and a lived experience is characteristic of the way these poems work on the reader.

Like Reznikoff and Rukeyser before her, Forché successfully created a poetry of witness: in her case, she found a way to combine a poetics of rendered experience with political engagement. One way in which she does this is through the regular shifting of perspectives. This is most evident in the dialogue poem ‘Return’ – or in her use of figures such as Claribel Alegría or Elena as a particular lens. But it is also done on a micro-level in her subtle use of pronouns. There is the ambiguous ‘we’ towards the end of the opening poem, which might refer to herself and her travelling companions (as in the first line, ‘We have come far south’) or might refer to Californians (or Americans, more generally), but manages to include both the reader and herself in the criticism she is making. There is the repeated use, in ‘Return’, of a micro-second of pronominal uncertainty (‘So you know / now, you said’). The reader hesitates as the referent shifts as she crosses the line-break. These changing perspectives and the repeated destabilizing of the reader at the start and end of the journey reflect Forché’s own self-questioning through the sequence: while still presenting the personal as the site of resistance, she insists on attention to the larger structures within which that personal life is lived.

The Country Between us was the product of a period of time spent in El Salvador: immersion in the culture of the country provided its experiential basis. But what happens to a poetics of witness in a time of lock-down? What happens when we can no longer cross the border to that other country whose poverty and inequalities remind us of our complicity – whose life, beliefs and customs makes us question our own?

Robert Hampson was Professor of Modern Literature and is currently Professor Emeritus at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is an expert on Joseph Conrad: the author of three monographs on Conrad, two co-edited collections of essays and editor of several editions. He is Chair of the Joseph Conrad Society (UK). He is currently working on Conrad, borders and transnationalism. He is also engaged in contemporary poetry as practitioner, editor and critic. He was long-listed for the Forward Prize and has co-edited volumes on contemporary British poetry, London poetry of the 1970s, Frank O’Hara, and Allen Fisher.